Welcome to Venture Visionaries, a brand-new series brought to you by Outlander VC. Hosted by Paige Craig, Managing Partner at Outlander VC, join us as we sit down with some of the most influential investors in the industry, uncovering the secrets behind their success and learning how they navigate the ever-changing landscape of investing.

This month, we had the pleasure of talking with Mercedes Bent, Partner at Lightspeed Venture Partners! Bent is not only an incredible investor, but a 2X founder and managing team member who has helped startups grow from the inside from $2M to over $100M in revenue. Since her early days sitting at the dinner table brainstorming fun hypothetical inventions with her father, she has lived and breathed innovation.

Bent invests in consumer, FinTech, EdTech, LATAM, & multicultural regions and founders including Flink, Outschool, Stori, and more. In 2016, she was named a “40 Under 40 for Tech Diversity in Silicon Valley” and in 2021, WSJ named her one of 9 “Women to Watch in VC“. She has an MBA and a Masters in Education from Stanford University and an AB from Harvard University. She is an African-American of Bermudian, Grenadian, and Colombian heritage and in her free time she enjoys playing board games & off-roading in her Jeep.

Below, we’re going to unpack one of the key traits that Bent looks for in winning founders – a trait that can be crucial in the rollercoaster ride of entrepreneurship in order to build a successful business. Beyond what we uncover here, there were so many more gems in our conversation that it’s worth watching the full replay. The 1-hour chat flew by and holds incredible insights & tricks for founders and investors alike.

Let’s dive in!

As Bent points out, the only constant in startups is change and “you have to be able to scale yourself faster” than your startup to grow.

“The best founders in the world are thinking that every meeting, every opportunity that they interact with someone is a chance to learn,” Bent told us. Founders with this approach can accelerate learning cycles to quickly scaffold up their learning level. When repeated over and over again, this learning compounds and can dynamically help founders keep up with the scale of their businesses.

For best practices in steepening a founder’s learning velocity, Bent walked viewers through a great educational framework:

In the real world, this could look something like:

For Bent, learning velocity isn’t just a checkbox either – it’s a mental metric that she actually tracks when speaking with founders from conversation to conversation. To illustrate an example, she highlighted Pamela Valdes – the first Teal Fellow from Mexico and founder of Beek.io.

When AI was having a resurgence in 2022, Valdes approached Bent saying, “okay, here’s how we’re going to incorporate AI into our product” and literally “a week later, she had hit up all of the top experts at OpenAI and Anthropic and showed me an actual prototype that she had built with a new feature and the product.”

A fast-learning, action-oriented founder can simply go so much further in a shorter period of time. And often, fear of failure holds a founder back significantly more than if they could simply fail quickly, learn, and iterate.

So how can founders develop a stronger learning mindset?

When a strong learning mindset is present, it can touch everything and everyone in a business. A genuine obsession with learning is infectious and can translate in pitches and conversations to help founders pass what Bent calls the “time test” (how long since she checked the time during a pitch). When we, as humans, feel like we are engaging in an exciting educational exchange, we lean in, ask questions, and can’t wait until the next conversation.

There are so many other incredible insights from our conversation with Lightspeed’s Mercedes Bent, including diving into other key founder & investor traits. Be sure to check out the full replay and sign up for our next livestream event, an interview between Outlander VC’s Leura Craig and Tim Young, the co-founder & general partner at Eniac Ventures!

You can RSVP for the 6/25 live interview now!

Over the last 15 years, I’ve funded visionary founders building everything from robot delivery fleets to web3 creator economies and everything in between. Excited as I was by every new venture, I quickly realized that—like our founders—expertise in every moving piece of the now 150+ investments was impossible and tactical advice was not Outlander VC’s role to fill. So instead, we learned to ask the right questions to support our founders in forging their way into the unknown.

First and foremost, founders must identify their startup’s North Star Metric, i.e., the #1 most important metric in the business. Then, build a plan that ladders up to their target NSM, including sub-goals like product roadmaps, hiring plans, operational optimizations, sales/marketing strategies, etc. Learn more about defining your North Star Metrics here!

With a target North Star Metric and plan in place, here are the seven key support questions we ask our portfolio founders to ensure they prioritize their startup’s success:

Much like the parable of teaching a man to fish, the best way to support your portfolio companies is not by prescribing tactical advice. Instead, asking these seven key support questions at least once a month trains founders to keep them front of mind as they prioritize their team’s efforts to maximize their startup’s success.

With in-person events returning, investor introductions will require more than the perfect cold outreach email. When you’re face-to-face with a prospective investor, finding the right opening to pitch your vision, convey traction, and make a clear ask is a tall order—especially at large events.

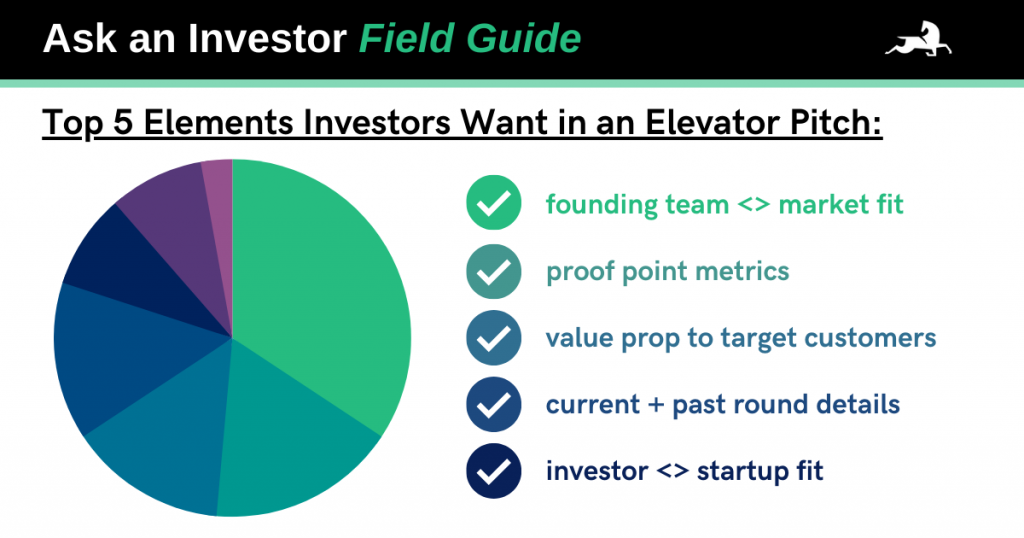

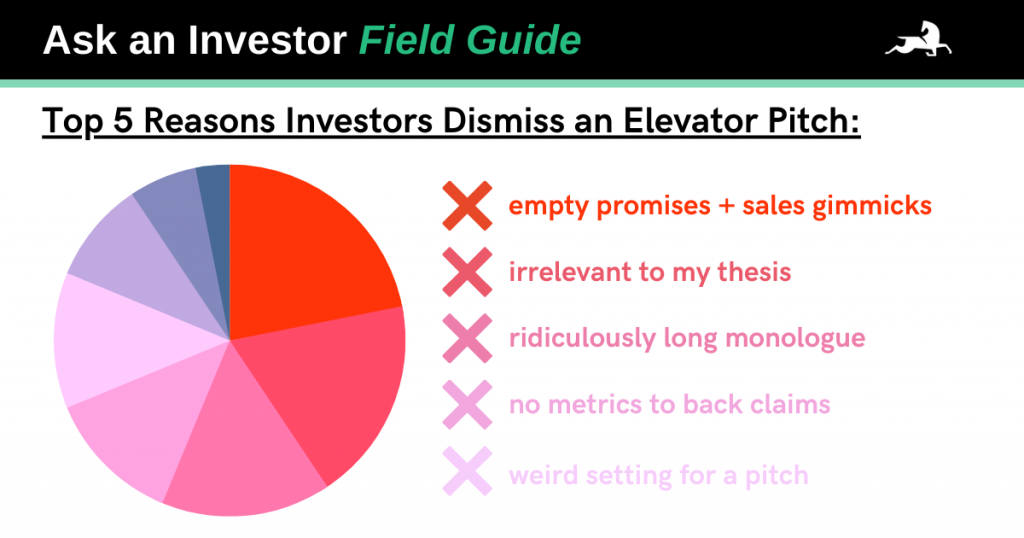

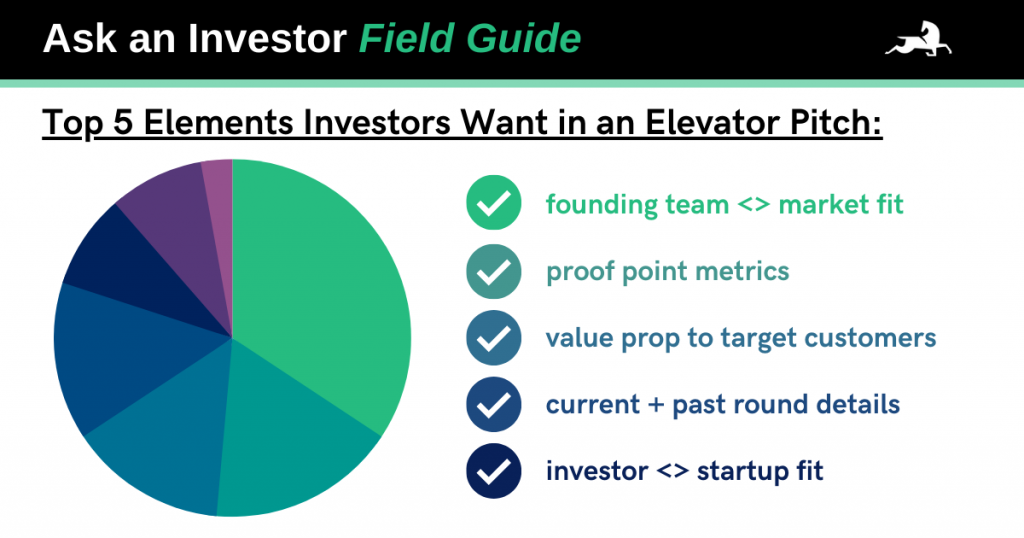

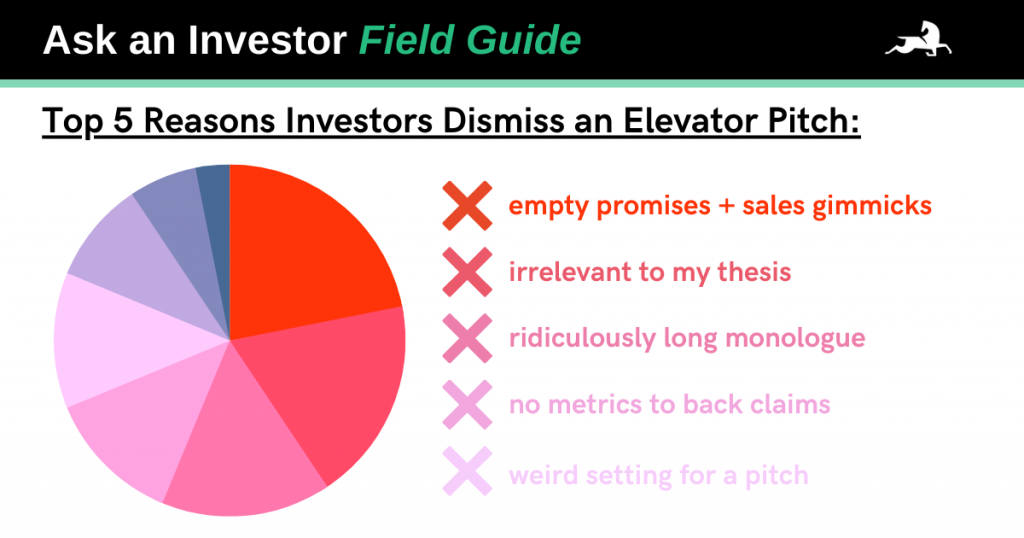

So, we surveyed our network of top-tier investors to see which in-person introduction strategies Do and Don’t work to help you stand out from the crowd.

To make a good first impression, avoid bathroom pitches, interrupting family occasions, or any tactics that border on stalking. Trust us—these tactics are a huge turnoff and only serve to hurt your cause. Instead, look for moments when there’s a natural opportunity for an introduction.

As with all networking, people are more likely to engage with folks they like and want to be helpful to, so a good first impression works in your favor. When in doubt, ask about the investor’s current focus or interests, then see if there’s a good fit between their response and what you’re building as a segue to your pitch.

The smartest founders know their audience and tailor their pitches accordingly. Convincing an investor that your startup fits their portfolio is key to securing a meeting. So, do your research via LinkedIn, Crunchbase, etc., to understand each fund or individual investor’s thesis and past investments to make the case for a perfect fit. The more relevant connection points you can draw, the better.

Your elevator pitch should succinctly touch on the scope of the problem, your vision for a solution, your founding team’s unique insight, product-market fit, and the dominant value proposition to your customer or user. Try quantifying your value proposition to further emphasize traction and make your solution tangible, i.e. save x% of time or increase revenue by x%. Explain your solution as it is today and how you predict it will likely develop over the next 3+ years. Once those bases are covered, don’t forget to ask if they have any questions!

Taking a chance on a founder comes with inherent risk. To mitigate potential wild cards, investors are also screening founders for honesty and transparency. If a founder seems to be withholding or misconstruing information, it’s a pretty big red flag. So stick to what you know.

While you want to appear confident, many investors note that overcompensating in the following ways can quickly kill interest:

Whatever you do, don’t leave an investor wondering, “What is the ask from me right now?” To transition to your ask, share how much you’ve raised to date and any key investors you’ve already lined up. If you’re currently raising, make the terms of the round clear. Be specific in your ask and remember: the worst they can say is no.

To recap, keep these 10 things in mind before you approach a potential investor:

These may seem like a lot of Do’s and Don’ts to juggle, but the bottom line is simple: be clear, concise, and courteous of an investor’s time. Remember that the primary goal of your cold introduction is to pique their interest enough for a call or a meeting, so focus on being straightforward and factual without getting too far down in the weeds.

Next, check out the Ask an Investor: Cold Outreach Do’s + Don’ts Field Guide to craft the perfect follow-up email!

As an investor, I’ve seen a lot of startup pitches—the good, the bad, and the ugly. And as a former founder, I feel for them. I know how daunting it can be to take the vision in your head, condense it into a clear explanation, and get others to quickly believe in it too. Early on, I also struggled to succinctly communicate the vision I had for my company.

At Outlander VC, I combine my experiences as a founder and investor to help our portfolio companies perfect their pitches. These are some of the best tips and tricks I’ve learned along the way to prepare, perfect, and present your pitch so that investors want to hear it.

When you’re raising capital in the early stages, there isn’t much of a company to pitch yet. It’s just a few folks, an idea, and maybe an MVP. You probably don’t have customers, users, or meaningful quantitative data to inform the investment decision.

Early-stage investing decisions come down to evaluating how the founders answer the following questions, based on Outlander’s Founder Framework model:

Ultimately, early-stage investors are looking for a founding team worth betting on. Early-stage founders with compelling answers to the above questions demonstrate they have the intelligence, vision, character, and ability to execute necessary to build on their thesis and scale it into an industry-disrupting powerhouse.

Helping early-stage founders perfect their pitches, I’ve noticed a common disconnect: passionate founders who eat, sleep, and breathe their startup perceive the cadence of their pitch as clear, confident, and compelling—but investors often hear it differently.

For example, I was recently working with a founder on his pitch. He has the big vision and passion necessary to convince investors, but his delivery needed fine-tuning. Seeing is believing, so I suggested he record his next pitch and send me the recording.

The next time we spoke, he told me that he’d realized, watching the recording, that he’d had no idea how his pitch sounded. With the recording, he could self-critique and correct every part of his delivery he didn’t like. He could sit on the other side of the pitch deck and, for the first time, see exactly what his potential investors would see.

We decided to take this exercise a step further. Instead of booking time with peers to get their feedback, he sent them links to his recorded pitch. Recording his pitch practice worked well for several reasons:

Recording yourself isn’t novel—it’s a time-tested tool, and it’s still highly effective. Plus, with new WFH tools like Loom’s simultaneous camera, microphone, and desktop recording technology, sharing a virtual pitch has never been easier. If you want to perfect your pitch, consider tapping “record” first!

As I said, I’ve watched a lot of pitches. The most painful to watch are those where the investor struggles to understand what the founder is trying to communicate. But I’ve helped founders whose pitch crashed and burned in the morning regroup, adjust their approach, and nail the same pitch a few hours later.

The difference? At the beginning of the second meeting, the founders sought to understand their audience by asking a few simple questions, which allowed them to deliver the pitch in the way the audience preferred. The change was small but powerful.

Here are a few questions founders can ask to understand their audience:

Understanding the audience goes a long way toward helping founders communicate effectively and gain support. The questions above will help accomplish that, but it’s by no means an exhaustive list. Plenty of other questions would also work. Regardless of what you ask, I’d limit it to two or three questions.

Now that you’ve perfected your pitch, we want to see it! Here’s what you need to know:

Outlander VC is inviting the most innovative early-stage tech startups in the United States to out-vision, outsmart, and outpitch the competition at OutPitch 2.0! Apply now to compete for $100,000 investment from Outlander VC during the live event on December 7, 2021.

For more expert advice on building and scaling your startup, check out our event library and Field Notes.

First impressions matter—especially when you’re making a cold introduction to a potential investor. And in order to make sure you put your best foot forward as a founder, you must broaden your scope from merely raising funds to building lasting relationships.

We surveyed our network of pre-seed investors to determine what elements of a cold outreach are most likely to work in a founder’s favor and what aspects of a cold intro compel them to immediately delete. Here’s what they shared with us:

These may seem like a lot of Do’s and Don’ts, but the bottom line is simple: be clear, concise, and courteous of an investor’s time. Remember that the primary goal of your cold introduction is to pique their interest enough for a call or meeting, so focus on being straightforward and factual without getting too in the weeds. Finally, if you want to grab their attention, do your research and personalize your pitch!

For more expert advice on building and scaling your startup, check out our event library and Field Notes.

For February’s Outlandish Speaker Series, we spoke with Lo Toney of Plexo Capital.

Lo Toney is the Founding Managing Partner of Plexo Capital, which he incubated and spun out from GV (Google Ventures), based on a strategy to increase access to early-stage deal flow. Plexo Capital invests in emerging seed-stage VCs and invests directly into companies sourced from the portfolios of VCs where Plexo Capital has an investment.

Prior to founding Plexo Capital, Lo was a Partner on the investing team at GV where he focused on marketplaces, mobile, and consumer products. Before GV, Lo was a Partner with Comcast Ventures, leading the Catalyst Fund and working with the main fund focusing on mobile messaging marketplaces. He also worked with Zynga as the GM of Zynga Poker with full P+L responsibility for Zynga’s largest franchise at that time. During his leadership, web bookings increased by over 150% with margin expansion. Lo has also held executive roles with Nike + eBay as well as startups funded by top-tier investors.

Lo received his M.B.A. from the Haas School of Business (University of California at Berkeley), where he completed the Management of Technology program: a joint curriculum program with the College of Engineering. Lo received his B.S. from Hampton University in Virginia.

Lo spoke with Outlander’s Paige Craig about investing in emerging managers, diversity in venture capital, and the future of work. Listen to the full conversation or hit the highlights of our Q&A:

This national conversation about race wouldn’t have really gotten to the point it’s at today without the unfortunate events of last summer. Without question, I think everyone can agree that this wave of protests felt different. But I also think there is a feeling—and I’ve heard it and I feel it as well—that it may be kind of waning now, that it is just a moment. We don’t want that to happen. We want to see it turn into a movement.

So we’re staying focused on these issues, especially in highlighting the great things that happen when we can get capital into the hands of these Black GPs who data shows often have more diverse portfolios than their peers. More capital into the hands of diverse GPs is more capital into their more diverse portfolios, and once their portfolio companies get access to that capital to execute their strategies, those diverse founders also go down a wealth creation path which ripples out into their communities.

Data also shows that these diverse-led companies also end up hiring a more diverse early employee base. And when those diverse employees have access to capital, the opportunities change for them because they’ve got a financial backstop they didn’t have before. They can go and start a company or invest in one of their peers. And then capital goes back to the GPs, and if the GPs have enough liquidity events, they go down the wealth creation path and capital goes back to the LPs. This model leverages a great strategy to drive alpha and produce returns with the by-product—which I’m really passionate about—of diversifying the ecosystem is working, and we should all triple down on this.

And this is very similar to what happens in a geographic ecosystem, right? Just look at what’s happening in Atlanta: money paid to employees of bigger businesses is used to start companies investing in early-stage startups, thus creating a whole ecosystem for startup funding. Atlanta is really interesting because we can actually see that vertical ecosystem built around people of color, Black people in particular. So, I look at places like Atlanta as a kind of proof of what can happen when there’s inclusion at the earliest stages of the development of an ecosystem.

“Atlanta is really interesting because we can actually see that vertical ecosystem built around people of color, Black people in particular. So, I look at places like Atlanta as a kind of proof of what can happen when there’s inclusion at the earliest stages of the development of an ecosystem.”

— Lo Toney, Founding Managing Partner, Plexo Capital

Based on all the individual anecdotes that I’ve seen, it is clear that more capital has gone into Black-led companies within the past 12 months, but not as much as we would like. I’m anxiously awaiting the actual data to come out because I think what we’ve seen is probably an increase, especially in later-stage companies like Calendly in Atlanta or Squire in New York. The most visible examples have been at the later-stage companies, where we had never really seen any dollars go into Black-led companies at the later stages before.

Part of the problem is also the lack of Black venture capitalists. Then within the Black VCs, there are even fewer Black limited partners, and within the Black LPs, there are only really two types: the majority being professionals that work for the endowments and foundations of the world and the minority of Black LPs are people like me who are controlling their own pool of capital. And we don’t tend to see as much activity by the pension funds in early-stage venture capital due to their obligations and liabilities to their constituents.

First and foremost, this is an issue that actually keeps a lot of potentially great GPs out of the market. One of our GPs actually told me about pitching a prospective LP—a retired venture capitalist—who listened to the GPs challenges and said, “Well, maybe you’re not rich enough to be a VC.” And I was shocked. First of all, there’s no data that I’ve seen that says the richer you are the better of a venture capitalist you’re going to be, right? But, to your question, there is a financial reality to being a successful venture capitalist as well.

We’ve estimated that it takes about $1-2M to get things rolling. And how do we get to that number? Well, it’s a combination of things. For one, foregoing their salary for what we estimate will take about 24 months from the time that a data room is open with an LPA until the final close happens. They’ve got to finance their lifestyle so they can focus fully on raising a fund, which is really difficult especially for an early manager. If you’re an emerging fund manager, you might have 50 LPs to 100 LPs, and that alone takes a lot of hustle over a long period of time even pre-pandemic. There are travel, pre-marketing, and hiring expenses, not to mention one of the bigger expenses, if it’s not able to be deferred, of legal aid for fund formation. All of which a GP is paying out of pocket. Then, once that first close happens, there is the ability to recoup fund formation.

Usually, for a smaller fund, I’d say you probably no more than $250K or so. You’re likely not going to recoup any of that lost salary or travel expenses, but the legal expenses are non-negotiable. And to your question, Paige, your salary is not going to be what it was—if you’re lucky, it’ll be half or maybe a third until you can stack a couple of funds to have stacked management fees. And, then, you’ve still got to turn around and pledge 1-2% as the GP commit, which is a significant financial hurdle for a lot of people to enter the space.

I’ve seen people handle this a little more creatively than how I answered above. I know I was lucky in that I was able to basically be an entrepreneur in residence while I was working on my fund at GV. And if you can find an opportunity to work inside of a fund, I highly recommend doing it to get a little bit of salary and a little bit of infrastructure as you build. And to touch on diversity again, that’s a great way that firms can help diverse emerging managers, right? My other recommendation is to see if you can defer your legal fees. If you can go to one of these larger shops, they might be willing to defer the legal fees, which is a big help to not have to pay those until after there’s a close.

“One of our GPs actually told me about pitching a prospective LP—a retired venture capitalist—who listened to the GPs challenges and said, “Well, maybe you’re not rich enough to be a VC.” And I was shocked. First of all, there’s no data that I’ve seen that says the richer you are the better of a venture capitalist you’re going to be, right? But, to your question, there is a financial reality to being a successful venture capitalist as well.”

— Lo Toney, Founding Managing Partner, Plexo Capital

At the end of the day, our objective is to make sure our Plexo Capital GPs can make that transition from being a great investor to a great fund manager. And there is a difference. It’s one thing to be able to pick and support portfolio companies, but a whole other ball-game having investors in your own fund and managing that process with other people’s money. For instance, it requires having lawyers craft the LPA, negotiating that LPA to meet objectives with the investors, creating a cadence of communication that makes sense for your investors, reporting that gives your investors the information that they need, the insight into what it is and isn’t working with our strategy, putting together a go-to-market strategy for a fundraising process, and more. All of those things don’t really have anything to do with being a great investor. Those are skills of a great fund manager, which is what we’re really trying to help our GPs transition into.

It really just depends. My first thought is that this goes back to something called strategy drift, which is when a company doesn’t change with technology or with competition and continues to do business the same as it always has been doing it. And the one thing that LPs don’t want to see is strategy drift. For instance, when you look at the data about what actually produces the majority of manager churn inside of a portfolio, it’s not usually tied to any fund performance metrics but more often a combination of strategy drift, general partnership issues, and poor communication—all elements that really are more about whether or not you’re a good fund manager, not a great investor.

So, my feedback for this emerging fund manager is to go in with a thesis and a strategy, then execute against it. In that strategy, there must be lessons learned in Fund I that are going to support the elements of the strategy of moving forward into a successor fund as well as any required modifications. The key is the ability to be able to provide that insight to the prospective investor as to why these decisions are being made, so really focus on being consistent in your strategy while also recognizing and adapting the lessons learned in Fund I.

Also, keep in mind that a lot of times when a fund manager is interacting with an LP, the LP is going to want to build a relationship over time because we’re preparing for multi-decade relationships. And it may be the case that the LP looking at the current fund is not going to invest until the next fund because they want to see a full cycle, right? Your ability to demonstrate the lessons learned in Fund I that made you stick to your strategy and even make necessary tweaks to that strategy is critical to building trust with your LPs.

When I think about the things that were gaining traction pre-pandemic, there was a lot of focus on delivery services that enabled consumers to reclaim their time. Then from an operational perspective, we were thinking about the fundamental shifts and logistical measures that needed to happen to get those things to consumers quickly and with minimal effort on their part.

For example, we’ve invested in this virtual kitchen company, which looks at all the data around people’s preferences for types of food, where those people live, and then creates a hub-and-spoke model with ghost kitchen restaurants that look like they’re brick and mortar in terms of their online presence. But they’re not! They’re solely geared towards UberEats-style delivery. Pre-pandemic, we saw these ghost kitchens climbing higher and higher on the algorithm because of all the data that they’re using to understand preference and location. Then the pandemic hits, and all of a sudden there’s a steep rise and increase in demand for that type of service.

For consumers, there’s been an acceleration in these delivery services, as well as anything to do with the screen. Driven by the insatiable demand for content from Netflix, Amazon Prime, and Disney+ and the uptick in playing video games together and remotely, the demand for an infrastructure required to be able to deliver those services has also increased.

On the enterprise side, think about all of the naysayers that were laggards when it came to accepting remote work and a distributed workforce. There was a psychological barrier as well as a financial barrier because even if people agreed that it was going to be productive, they didn’t necessarily have the infrastructure in place to be able to support remote work or a distributed workforce. But then the pandemic hits, and now the naysayers have been forced to deploy billions of dollars into building that infrastructure. It would have taken years to get the investment that we’ve seen into all the infrastructure required to have a secure system for remote access work, but we’ve seen this massive acceleration when the pandemic first started.

We’ve seen massive amounts of money going into these different services for both consumers’ and for enterprises’ new normals, which I think are likely going to persist long-term. That’s where a lot of new opportunities are going to happen. The downside, of course, is that these great new innovations are juxtaposed against the pain and suffering of so many people across the globe. So, for investors, it’s really important to think about the things that we can invest in that can help narrow socioeconomic gaps as a by-product of what they do as opposed to widening those gaps.

The Partners at Outlander VC share one very important commonality: experience as founders. Each of us turned to venture capital to solve a problem we faced while sitting on the other side of the pitch deck, and we are now uniquely positioned to mentor founders based on this shared understanding. From the barriers facing minority entrepreneurs to the pitfalls of trial and error, here’s how our team of founders-turned-venture-capitalists is using their founder experience to guide their investing, plus their advice for founders just starting out.

As a female founder raising venture capital, I was pitching to a fairly homogenous subset of men to which I was a stark minority. At networking events, I was disheartened by the lack of gender or racial diversity (especially where those identities intersect) among my fellow founders. In recent years, it’s become more widely-acknowledged that the tech startup ecosystem is not diverse enough. However, just talking about this lack of diversity is also not enough.

We know that 65% of venture capital firms have no female partners and 81% have no Black investors, which directly impacts how they source potential investments, evaluate founders, and fund ventures. At Outlander, we believe that who sits at the decision-making table matters. We believe that one of the best ways to diversify the tech ecosystem is to diversify who is writing the checks, so that is exactly what we did.

On a more day-to-day level, one of the things I work on with Outlander’s portfolio companies that I learned as a founder is ruthlessly prioritizing where you invest your energy. There will always be too much to do and never enough time, so it’s crucial that founders intentionally prioritize progress in areas that will get their venture to its next important milestone.

“At Outlander, we believe that who sits at the decision-making table matters. We believe that one of the best ways to diversify the tech ecosystem is to diversify who is writing the checks, so that is exactly what we did.”

I didn’t start my military business to make money; I started it to solve big problems with a crazy idea that I knew would make a massive impact. And when I transitioned to tech investing, I realized that every founder I met was just like me just years earlier: motivated despite a world of naysayers that can’t wrap their heads around such an ambitious vision for the future and also very much in need of support beyond just capital.

As we point out in Outlander’s Founder Framework, founders are psychologically unique in their bigger-than-life visions and the need for emotional resilience, which is why former operators often make the best mentors and investors: we get what it’s like to willingly embark into uncharted waters when everyone ashore thinks you’ve lost your damn mind.

As a founder turned investor, my advice for any founder is to experiment at the intersection of their passions and capabilities—this will ensure your venture offers a truly innovative and unique insight into the problem you’re trying to solve. It’s not enough to just find a problem and set out to solve it; without an underlying motivation, there is less reason to push through when things inevitably get tough.

“It’s not enough to just find a problem and set out to solve it; without an underlying motivation, there is less reason to push through when things inevitably get tough.”

Though not a tech startup founder, I’ve been fortunate to walk the founder path in other industries. Throughout these experiences, I kept arriving at this conclusion: the companies I wanted to build were ones that 1) I truly believe will make a significant, positive impact in the world, and 2) the founders are uniquely positioned to build their vision of the future.

When I quickly learned that becoming an expert in all my areas of interest was unrealistic, I realized that venture capital offered the perfect modality to scale this desire. As an investor, I am in my happy place: working with brilliant minds who are passionate about solving big-impact problems across a myriad of industries. Investment fit or not, my mission is to help founders succeed, and I revel in acting as both a sounding board for their business challenges, as well as making introductions to potential resources, talking through life, and much more.

Reflecting on my time as a founder, I definitely could have been more honest with myself about my strengths and weaknesses and worked to build a more robust support network. I often encourage our founders to lead with their vision of the future and the unwavering belief that they are uniquely positioned to build that vision. However, this unwavering belief is not to be confused with the unrealistic expectation that founders be experts in every aspect of their startup and execute every operation perfectly (far from it!), but knowing when to assess their gaps and rely on the support system they’ve built is crucial to their success.

“As an investor, I am in my happy place: working with brilliant minds who are passionate about solving big-impact problems across a myriad of industries. Investment fit for not, my mission is to help founders succeed.”

My founder experience is one I hear often as an investor: I didn’t know what I didn’t know until it was too late. As a non-technical founder, I did know I had certain knowledge gaps related to technology. I didn’t realize I also had other big gaps in relationships, capital, and start-up expertise that I’d have to fill to scale my company to over $10M in annual revenue.

I like to joke that during those years of trial and error I personally stepped on most of the hidden landmines that lie in wait for new founders. Now, as an investor, I’m eager to share my experiences with founders to help them stay on safe ground and scale their ventures bigger and faster—and with less angst—than I did mine.

I learned a lot of timeless lessons during my entrepreneurial journey, many of which apply to all leadership roles, not just founding a tech company. An important overarching one is that you must be self-aware and brutally honest with yourself. You won’t be great at everything. That’s okay! Accept it, and don’t try to do it all yourself. Purposefully surround yourself with advisors, cofounders, and peers who complement your weaknesses and your skillset. No one will expect you, the founder, to be an expert in every aspect of your company. You’re expected to lead, a big part of which is equipping your company with the experts it needs to thrive.

“No one will expect you, the founder, to be an expert in every aspect of your company. You’re expected to lead, a big part of which is equipping your company with the experts it needs to thrive.”

With 20+ years in tech as an operator, serial founder, and startup advisor, I’ve observed the process of raising startup capital from countless case-studies, and what I keep running into is a dissonance between the exceptional women of color founders I meet and the inaction of investors.

Note that I am not citing a lack of opportunities, but that fewer investors have been willing to take a chance on a marginalized founder’s vision: it runs the gamut from microaggressions in interviews to dismissing ventures aiming to revolutionize multi-billion dollar industries that simply do not apply to the majority of (white, male) investors. I’ve seen and experienced first-hand the gap between marginalized founders and the support they need to grow their ventures, and I wanted to be a part of the solution.

To bridge this gap, I work to educate the tech community about the untapped potential of not only these underrepresented founders but also the untapped potential of the Southeast. In that same vein, my biggest piece of advice is really for investors, and it’s simple: don’t count us out. If you want to invest in truly exceptional founders, start making a conscious effort to cultivate relationships with investors and founders who don’t look or talk like you. If you want to invest in startups already changing the world with their vision, forget what you thought you knew about the South. We’re here, and we can’t wait to show you what we’ve been working on.

“If you want to invest in startups already changing the world with their vision, forget what you thought you knew about the South. We’re here, and we can’t wait to show you what we’ve been working on. ”

These founder-turned-venture-capitalists are not only uniquely positioned to mentor Outlander VC’s portfolio companies from a place of experience and innate understanding, but we also bring a founder’s mentality (vision, intelligence, character, and execution) to how and why we invest. At Outlander, we invest in the brightest founders with game-changing visions for the future because we know what it’s like to be on the edge of something big.