Growing up in his family’s apartment in the Van Nuys neighborhood of Los Angeles, Bardia Dejban learned at a young age to bounce back from tough times. By the time he turned eighteen, he had survived multiple near-death experiences from which he pulled himself back to full health. Those incidents seared a distinct appreciation for seizing the most of life as a result – he realized more intimately than most that life is precious and time-limited.

His father was an Iranian immigrant who had brought the family over to the States, worked three jobs to provide for them, sent them to college, and eventually built his own successful construction company. The context of his family’s work to stake their own claim in a new country and the medical challenges he overcame made Bardia committed to taking risks of his own and devoting his time to making a mark on the communities around him.

In his case, the medium for building became software. He learned how to build websites in his teens and by age twenty had fallen in love with creating Visual Basic applications for local businesses (along with some full-featured e-commerce sites). By his mid-twenties, he was creating software for some of the largest financial institutions in the United States.

Nowadays, he is building his second company, an “engineering intelligence” platform called Codalytics. It began as a plot to organize information on companies’ tech teams for quick digestion in the way Salesforce organizes the activity of sales teams. Two years ago, running the software development studio Lolay – his first company – he was confronted daily with the challenge of tracking who among his twenty-two engineers was making progress on each project. With a background running engineering teams at Intuit, eHarmony, and IAC, the lack of easily visualized information on his teams’ activity within code repositories was familiar. “Anytime a team of engineers gets past ten people,” he explains, “communication becomes a rapidly increasing challenge.”

Bardia wanted to be able to log into a portal that would seamlessly visualize activity across code repositories, broken down by employee, project, language, and other tags. Fellow engineering managers he knew expressed the same problems and desire. He couldn’t find an existing solution that satisfied his criteria, however, and in July 2013 he made the jump to go build it himself alongside a friend he had worked with as a client.

Codalytics has not been the overnight success that the press often loves to mischaracterize startups as. In fact it’s still in the gritty days of learning from mistakes and fighting to relaunch with a new, simpler product. Two years after founding, Bardia is leading the relaunch as a solo founder, having lost his co-founder and first hire in early summer. The problem he is targeting is very real, he knows, with a pain point confirmed by nearly every engineering executive he meets; he just designed the wrong initial product to satisfy it.

The problem he and his team ran into was attempting to do everything well but in the process not doing any one thing exceptionally. “At the end of the day, companies big and small who piloted Codalytics really liked the platform” says Bardia, “but they didn’t think it was developed enough yet to pay a $25,000-100,000 yearly Enterprise SaaS subscription.” Running out of money and still having so much work to do in order to meet the pilot companies’ specifications, Bardia’s co-founder and first hire – concerned about the impact of losing stable income on their families – decided to part ways. The venture had seemed to be taking off then had rapidly hit the breaks as answers from the engineering executives came in saying they wouldn’t pay yet. The sudden shift in circumstances really shook Bardia.

That’s when he came across a blog post by Intercom’s Des Traynor that struck a chord. It made a cooking analogy to emphasize a key point: you should never bake cake when all you need is a cupcake…start with a small version to figure out what you like before using that recipe for an entire cake. That comparison, right at that specific time, was an “ah ha” moment for Bardia.

Software startups are inspired by a grand vision for the product they can build and the impact it can make in its market, and that creates a temptation to think ten steps ahead instead of one. However, it should start with smaller, ultra-practical initial steps, maybe by developing the right kind of API. The journey from leveraging platforms like Google Apigee for creating and managing APIs to designing a market strategy takes time. Only careful planning can get a simplified product into the hands of paying customers and provide proof of your concept.

Founders need to start by shipping barebones products that they are a bit embarrassed by and that constitute only a tiny fraction of what their team envisions the product becoming. The fastest way to build out the long term product successfully is to get an initial foothold in the market and learn through firsthand observation what customers’ real needs are.

So Bardia went back to the drawing board and decided that instead of making the Codalytics platform more advanced, he would pick one feature, cut out the rest, and do that one thing really well. The most simple incarnation of the Codalytics vision was its daily summary email providing an engineering manager with basic metrics on their team’s activity across multiple projects. He stripped it out, created a new landing page at Codalytics.com, and began offering it as a standalone product.

Locking major corporations into six-figure SaaS contracts for a comprehensive platform had resulted in 8-12 month sales cycles and extreme pickiness in what they were willing to pay for. But a daily email providing distinct and concrete value for $5 per month (per project)? That is proving to be a tool individual engineering managers will happily subscribe to and just pay for with their company credit cards.

Returning to both companies he had pitched previously as well as with new organizations, Bardia brought Codalytics back to life. The daily digest that customers receive gives an organizational view of their GitHub repositories and contributors to them, sorting each engineer’s total commits, the overall progress (or stalling) of specific projects, and links to compare more detailed analytics. It’s his wedge into the larger opportunity for engineering intelligence technologies.

Bardia is humble and emphasizes how much work there is still to do – he is fighting to hit targets of 100% month-to-month sales growth and 90th percentile net promoter scores. His reboot is making strong headway: new customers (with anywhere from 5 to 1,000 internal technical projects) are signing up, and nearly every one of them is opening the digest email every single day. Codalytics is about to launch an enterprise installed version of their software as well so large companies can use the daily email digest while pulling (and protecting) data from behind their own security walls.

Bardia is very focused on short-term sales and refining the core email product, but he also has a clear step-by-step path in mind for Codalytics’ growth in 2016. Once the email product hits a threshold of subscribers that Bardia has privately set, the next feature in the company’s pipeline is a patented scoring model that leverages Codalytics’ data to rank the output of a company’s engineering talent. It tracks the speed at which every engineer in a company works, the skill they do it at, and the number of revisions their code requires (by them and others). It will show that while one engineer might take a little bit longer to write code, they do it exceptionally better than their peers, who have to revise their work numerous times after the ‘first draft’. This system will give managers concrete data to understand how each member of their team works at a level of detail that hasn’t been readily available until this point. It will also benefit the individual engineers by giving them insight into how they work and where they can improve.

Despite the alternative path to go back into a lucrative tech executive role, Bardia is insistent on building the go-to solution for engineering intelligence and is confident in Codalytics’ growth potential now that it’s back on track: “it feels very different this time around – companies are getting value from the daily email, opening their wallets and asking what’s next in the roadmap.” Long-term, he wants Codalytics to evolve into a platform of developer tools that solve a number of needs through either one integrated product or several standalone ones. And he wants the company’s tools to help not only engineering managers but eventually every software developer on a team as well.

“I still have the same ambitious goal I originally set out with,” he shares, “but now with a concrete plan for making it happen…and not all at once, but one step at a time.”

Investing in seed stage startups can be exhilarating and highly lucrative, but it can also be incredibly risky and time consuming. Identifying the most promising new companies requires a lot of cutting through the weeds – I interact in one way or another with well over 2,000 entrepreneurs a year and take meetings with over 200 of them, all in the process of finding just the 15 I’ll invest in. The reality is startups need money for all kinds of things… most of these expenses are rarely considered by those involved until they actually have to pay for them. Would a novice really be aware of how much Verisure charge for a commercial alarm system? The likelihood of this is low.

When I first began investing, I wasted a lot of time. Tracking down the most promising entrepreneurs was a crapshoot and I didn’t know where to start. But as I developed as an angel investor over the last 8 years however, and now in running Arena Ventures, I’ve recognized the pattern of where my investments come from…where I get the highest ROI on my time.

There are 4 activities you can do as an investor to get to the good deals most quickly: hunting, trapping, farming, and trading.

Hunting is outbound work – hustling at events and parties, scouting for products online, reading and reaching out to people. You go anywhere you can to find great people. You don’t have a specific target in mind, you’re simply looking for unique, brilliant founders. When you first start investing this will probably be the majority of your time until you have a reputation, network and better idea of what you want to invest in.

A good example of hunting is Klout: I found the earliest version of Klout in 2009 while scanning Twitter posts and then tracked them down via friends in Boulder who knew Joe Fernandez. I pursued Joe aggressively, and took him out for tacos and drinks where I could spend time getting to know him and ultimately close on a deal.

When new angel investors ask me where they should start, I recommend beginning with the industry they work in and know best – what’s missing in that market or can be done better? If you see opportunities, start asking around and researching online to hunt down tenacious entrepreneurs that are attacking it. Even if the people in your network don’t bring you an immediate result, you’ll be top of mind going forward if they meet an entrepreneur who impresses them. Search online, attend every possible tech event, go to hackathons, attend parties hosted by startups and investors – do everything possible to find unique and interesting founders.

Check out what these startups have to offer, how are they conducting their work? Are they using up-to-date systems and software? Are they making use of managed it companies for their tech needs? Do they have a set plan in place for how they want to grow and expand their startup? All of this can show you how serious they are and what you can get from them.

After a little time hunting on the startup frontier you can engage in your next deal activity – trading. In this stage you’re working with fellow investors and looking for specific deals that interest you; and offering your own deals up in trade. By now you have a small network, a little reputation, some ideas on what to invest in and a deal or two under your belt.

It’s best to approach other angels and VCs and initiate the trade: share your deals, your ideas, your thoughts. Often times these investors will share deals back with you. It’s usually not a formal “give me X and I’ll give you Y” type of trade; instead it’s a relationship with informal rules of sharing deals with folks you value and respect and they’ll (hopefully) do the same in return. And if not, don’t be afraid to ask “What are you working on? Any great deals I should look at?”

Even now after 7 years of investing I spend a great deal of time sharing my deals and convincing people to invest in the first rounds of companies like Wish.com (contextlogic back then), AngelList, Quizup, Klout, Livefyre, Plated, Laurel & Wolf, Honk and many more. But as much as I’ve helped others, I’ve also benefited greatly from investors trading and sharing with me. When Zimride pivoted to be Lyft years ago I asked (maybe “begged” is a better word) Raj Kapoor to get me into the deal; luckily Tim Chang and the Mayfield guys are awesome dudes, approved the “trade” and got me into the deal (and now just this year we worked together again on the Fitmob / Classpass deal successfully!).

While hunting & trading are outbound activities, trapping is largely inbound (i.e. people coming to you) and you have a clear idea of who or what you’re looking for. You set “bait” that will attract your targets and then you let great founders come to you. Here are a few examples:

A great example of trapping is Postmates. In 2011 Jeremy Gocke of Fliptu sent me this message:

From: Jeremy Gocke

You might have seen this already, but it’s your Uber for deliveries idea…

http://venturebeat.com/2011/09/13/postmates-disrupt-launch/

A month earlier I had invited Jeremy over to one of my happy hours and I told him I believed an “Uber for deliveries” should exist and it would be huge. His email led me to Bastian and I ended up investing two months later. I follow this tactic often – sharing ideas I want to exist – and then waiting for founders or investors to come to me. In fact just a couple weeks ago we invested in Mytable – for two years I’ve been telling people I’m looking for an “Airbnb for Meals” startup and I’ve looked at over 30 now! But this year I finally had the right team pitch me and we closed the deal.

So go out there and set some bait. Spread your ideas, host targeted events and get great founders to come to you.

Farming is largely an inbound activity (deals coming to you) but you don’t have a specific target or type of startup in mind. Instead you invest months and years helping other people; being a great investor to your founders; helping local universities, mentoring at accelerators, and being a valuable part of the community. You make an ongoing commitment to invest time and energy supporting the top people and programs in your city or industry and eventually the deals start coming to you. When that happens, make the most out of the opportunity. Also, remember to not make the costly mistake of not insuring the most important people for your startup with key person insurance (keypersoninsurance.com) because you don’t want to suffer any economic loss after putting so much effort into them.

Farming takes the most work, and the payoff is often years in the future; but it will eventually become one of your best sources for deals and set you apart from less experienced investors. Once you have a solid reputation, a trusted network and years of great deals, many founders and fellow investors will be the ones coming to you and sending you deals. That is what fortunately brought me the ability to be an early check into both StyleSeat (thanks Devin Poolman and Steve Jang) and Wish.com, which is now rumored to be a $3B+ “unicorn” (thanks Brian Wong!).

The best angels and venture capitalists are savvy at the full combination of hunting, trading, trapping, and farming, but it’s important for new investors to remember that being an aggressive hunter at the start is key. You have to build your early reputation and first-hand experience in order to enable you to get the most value out of the other three over time.

At Arena, we have been active investors in mobile-first marketplace startups – the sphere of startups using mobile apps to connect consumers with services they need at the press of a button. These marketplaces partner with a network of partners/contractors on the supply side to respond in real-time to customer demand for a given product or service in their city.

Laundry and dry cleaning is one of the most active spaces within the so-called “on-demand economy,” with (Arena portfolio company) Rinse as a major player in the market. The San Francisco-based company operates, however, on a unique model from competitors: they are available 7 days a week but have created a route-based model where they typically collect clothes from customers on a regular basis on the same two days each week between 8PM and 10 PM (either Sun / Wed; Mon / Thu; or Tue / Fri).

While other laundry startups prioritize speed, rushing through the cleaning process to get clothes back to customers within 24 hours, Rinse found that what consumers care about most is a) the quality of cleaning and b) having a service integrated into their life that picks-up and drops-off on a consistent cycle.

With a vision to eventually handle all aspects of clothing care, from dry cleaning to shining shoes, they are staking a claim as the highest quality cleaning service and integrating themselves into the weekly routine of loyal customers (who range from young professionals to busy families).

Founded in 2013, Rinse has built a strong initial foothold in San Francisco, and in March they took the jump to launch in their second city: Los Angeles. For any geographically-tied startup, the expansion to a new city is a critical point in scaling the company’s operations. It is high-risk to take the lessons and infrastructure you have only just figured out in your first city and immediately try to apply those to another one. I talked with Rinse’s CEO Ajay Prakash and Los Angeles GM Lonny Olinick to understand how they’re approaching the LA launch and what other entrepreneurs should consider when deciding whether or not they are ready to launch their second city.

Prove your model first.

For Rinse, the decision to add another city was not based on hitting a certain market share in one city first; it was about getting to the point where they felt like they had figured out how to scale the company’s operations while maintaining incredibly high customer satisfaction and retention.

Ajay and his team had to experiment extensively in the early days of Rinse to find product-market fit, including determining the right pick-up window and fleet logistics plus how to collaborate most effectively with local cleaning partners and with the Valets who are the face of their business.

“We realized that the acute pain point that Uber solves when you need a taxi, where on-demand is the right answer, doesn’t exist in clothing care. The pain point is chronic – you always have dirty clothes – and the way to remove friction is through a predictable schedule and consistently high quality service.”

Because of Rinse’s quality-first approach, they were very focused on growing in a controlled manner so they could maintain their standards for customer experience as they scaled. As well as using a questionnaire to help get the views and opinions of their loyal client base, they also found that the key to scaling a business like theirs, they say, is in managing the operational complexity, which starts with having solid processes and technology in place. The relevant technological practices are something that all businesses must have in place in order to help drive their company forward, as well as being able to keep up with the ever-changing digital world. Implementing sip trunk providers, communication systems, and the relevant internet protocols is something that they may want to think about doing first and they can expand from there. If done, this should greatly benefit their business. With the motto “slower is better, better is faster” they kept their focus on getting their core business model right in SF and on learning how to scale it in one city first. Although they were always focused on adding new customers, their key performance indicators centered on customer satisfaction, customer retention, unit economics, and partner satisfaction.

Rather than quickly hiring a large group of 1099-category freelancers to act as drivers on their routes, Rinse invested from the start in hiring their Valets as W2 part-time employees with a more thorough hiring and training process. “Our Valets are the frontlines of our customer experience, so we were very focused on hiring employees who would be great at customer service rather than simply looking for anyone who had a car,” explains Ajay. There are legal guidelines dictating the distinction between 1099 and W2 workers, and one of the key problems Rinse saw with 1099 networks like Uber’s is that the business isn’t allowed to provide much oversight or extensively train them. Because of Rinse’s priorities, they have invested significant time in training Valets from Day One and have built a system where the best Valets can take on mentorship roles for others or move into full-time roles on the Operations or Customer Experience teams.

By early 2015, Rinse was operating at full force in San Francisco and started eyeing its first step into another market.

When is the right time to launch in another city?

Ajay says Rinse started discussing expansion once growth in San Francisco took off and the team had proven it was able to confidently manage operations as it continued to scale quickly. They had grown rapidly since launching full service in September 2013 and had several thousand recurring customers (who were using Rinse on average twice or more per month), and had an ever growing team of Operations Associates and Valets making sure the nightly pickups and deliveries were seamless.

There’s a popular phrase coined by Y Combinator’s Paul Graham that new startups – especially marketplaces – need to “do things that don’t scale” in order to build their early traction. It’s a truth memorialized in tales like the Uber founders driving black cars themselves and the Airbnb founders filling inventory by duplicating Craigslist posts, and Rinse has stories of its own. But according to Ajay, “you’re ready to launch in another city when you can take care of your customers without having to ‘cheat’ like that anymore.”

When the team had reached that point themselves, they decided to start building a customer base elsewhere – both for customer growth and to prove the Rinse model could work outside of tech-forward San Francisco. “San Francisco is a unique city for startups because there are so many early adopters here who will try a new service and be extra forgiving knowing that the company is still figuring things out,” he said, explaining it was important to confirm their service would work well in other locations without that. So at a Board meeting in early 2015, Rinse decided to accelerate its timeline for expansion.

Ajay and his team considered several cities but settled on Los Angeles because of its proximity to the SF headquarters – if needed, anyone on the team could fly down to handle an issue within two hours. LA also boasts a large tech startup ecosystem on the Westside and Downtown, with tech employees who could act as their early adopters promoting Rinse to other friends.

Launching in Los Angeles.

Rinse sent one of its team members, Eliot Chang, to LA in March to start laying the groundwork for the launch, and then hired Lonny as its full-time GM in May so Eliot could return to oversee San Francisco operations. As Ajay describes, it’s important when you launch a new city to hire someone who has a local’s understanding: “it’s hard to quantify, but there’s a lot of value in local knowledge and pre-existing relationships” (from traffic patterns to the culture of different neighborhoods).

Rinse organized its initial LA rollout into four stages: an alpha test with locals they knew, an early beta test with friends-of-friends and some early adopters, a partnership-based “Friends of Rinse” campaign, and then finally a shift into outbound marketing to the public.

The first stage included solely people the Rinse team actually knew: investors, friends, and other contacts who would be understanding of any mistakes and would take the time to give them thorough feedback. While the LA operation would benefit from extensive lessons learned and infrastructure built up north, it was still a start-up operation building a presence in a new city from scratch. Rinse wanted to make the inevitable early mistakes in a safe environment and give its first Valets on-the-job training to learn the ropes.

Like in SF, they devoted extra time toward hiring the best qualified Valets, because those initial hires would not only be the face of Rinse to LA customers, but they would also be in charge of training the waves of Valets hired after them. “Customer service starts and ends with our Valets,” explains Lonny, “so we have a multi-step process for hiring that includes interviews, reference checks, and riding alongside them on test shifts.” All the early valets came to Lonny through referrals, encompassing a wide mix of demographics from college students to actors looking to make extra income in the evenings.

Once initial operations were in place and Rinse had successfully served a few dozen early customers, the team moved into Stage Two. That meant expanding to a wider network of friends-of-friends and some of the early adopters who had proactively waitlisted themselves online for the LA launch. Rinse included more zip codes in its coverage of LA (all still west of the 405) and determined the most efficient pickup/drop-off routes in its coverage areas.

After quickly proving that they could maintain high standards of quality and service as the additional demand developed over the second stage, Rinse shifted into Stage Three, where they accelerated customer acquisition among tech-minded residents who would be most receptive. For several weeks, Rinse reached out to other tech companies around the “Silicon Beach” ecosystem in Santa Monica, Venice, and Culver City to have them share custom referral codes (including $20 credit) with their employees. While not a core part of Rinse’s normal marketing strategy, it proved to be an effective tactic for acquiring initial users by the bucket instead of one-by-one. (Pro tip: according to Lonny, taking time to customize the landing page for each company’s referral link resulted in considerably higher conversion rate.)

Rinse is now in Stage Four, starting to publicly promote themselves to everyday Los Angelenos. By refusing to sacrifice on quality over the first five months in town (they closely monitor their Net Promoter Score and LA Yelp reviews), they have already generated substantial word-of-mouth leads from new customers. On the outbound marketing side, Facebook is their primary marketing channel and has proven to be an effective “billboard” to help build awareness early on. They are also starting to reach out to popular LA fashion bloggers to get in front of an audience that particularly values how their clothing is handled, and recently launched a Gilt City offer to attract fashion-forward shoppers in town. Lonny says the team is also considering a traditional advertising campaign using the exterior of public buses that run through their target neighborhoods, something that has been effective for Rinse in San Francisco.

Expanding to multiple cities of operation is a big step for any startup. There are countless stories of teams raising their first large rounds of venture capital and then expanding too quickly, only to have to withdraw from some of those locations a few months later. Rinse offers a valuable lesson in finding the balance between aggressive growth and refusing to sacrifice the customer experience or operational stability that allows that growth to keep accelerating.

Michael Schneider started exploring the idea of an “on-demand customer service” app just 60 days ago. Two months in, he has already raised a pre-seed funding round, made his first two hires, helped over 500 customers in 5 countries, and fields inbound inquiries daily from prospective new investors. A startup on this level has achieved so much in a short space of time, and as this progresses even further, the software will advance as well as how it will operate, with an updated business banking account, cloud-based software, etc. being used in a dynamic way.

As the fifth company Michael has started since high school, Service is the culmination of the lessons he’s learned about rapid experimentation and execution. While leaving his prior company, Mobile Roadie, and exploring ideas for his next venture, he committed to test different concepts and see which clicked with consumers.

The spark for Service itself came on a flight in April from Los Angeles to Miami. Michael witnessed a fellow passenger buy a Gogo wifi pass, only to find out that power outlets on the plane weren’t working. With a dying laptop, Michael watched the passenger waste over 20 minutes navigating American’s website to fill out a complaint form, and then do the same on Gogo’s. In an era when you can get a car, food, and dry cleaning on demand with the press of a button, he found it inefficient that consumers still have to waste hours of their time on hold and dealing with customer service issues themselves.

Four weeks later, with the concept still bouncing around his head, he decided to jump in and gauge the potential for an app-based service that seamlessly handles customer service situations on behalf of users.

“The single most important thing is to determine right away if what you’re going to put out into the world is valuable,” says Michael, “Everything is secondary to that. You should know within the first week whether or not what you want to build will have some value.”

It takes a long time to build and refine a product, and many startups dive straight into months of development only to discover upon launch that there was no demand for their product in the first place. Entrepreneurs need to find consumers in their target customer base and immediately test (with concrete results) whether they can provide a substantially better solution to a big pain point those people face.

All Michael needed to launch Service was a logo (to seem like a credible business), a Twitter account (to conduct outreach), and an online form (to field submissions). With a background in digital strategy, he recognized that he’d need to build immediate trust with consumers online in order for them to share the personal information (account log-ins, social security numbers, etc.) that Service needs to act on their behalf. He didn’t want a ‘startup-y’ name that sounds weird to normal people, and it would be clear to anyone viewing the company’s Twitter profile that Service was brand new, so he invested a lot in ensuring the brand looked credible. He paid out of pocket for the best designer he knew to create the logo and he found a way to get the “@service” Twitter handle.

To get started, he built a Squarespace page on the domain www.getservice.io in one hour (buying service.com costs $2MM), with nothing but the logo at the top and a form asking people to submit their email and customer service complaint. Then he took to Twitter searching customer service-related hashtags and mentions of major brands (like airlines and cell phone carriers) and began tweeting at people who were complaining about bad service.

Over that first day, however, he didn’t convert a single person to submit their complaint to the site. Dismayed, he went to sleep that night telling his wife that maybe there wasn’t a big opportunity after all. Then early the next morning he got his first bite. A woman in Chicago named Wendy had an issue with Expedia. He followed up to get her flight information, then called Expedia’s customer service line, and after that, Delta and then Frontier, to negotiate for a refund that Wendy deserved. One hour later, the airlines agreed and refunded her over $400.

Everyone that has a bad experience with Customer service or any issues should reach out to @service! They help! Thanks again!(:

– Wendy Walle (@whendii13) May 20, 2015

It was just one case, but her public praise for Service on Twitter motivated him to journey on. For several more days, around the clock he reached out to hundreds of people on Twitter – all the while testing different ways to pitch Service. He personally handled the cases of everyone who submitted their issue to the website. Six days in, he had 20 submissions and had solved over $1,000 worth of problems for 12 people, the majority of whom also promoted Service publicly on Twitter afterward.

Michael felt he was on to something. There’s still a lot of work to be done in building Service’s tech platform and scaling its operations, but at a foundational level he had validated that his model for Service could provide meaningful value to consumers. And with multiple people having proactively offered to pay him in response, he felt confident that there was a feasible business model.

“Twitter is the best market research tool a startup founder can have,” claims Michael as he talks about the ease of hunting the platform for targets. “Almost any B2C startup can easily find a group of potential customers on Twitter, tweet at them, and gauge the value of their pitch based on the response. Plus for B2B startups you have the ability to directly tweet at VPs and CEOs.”

Early testing with a barebones version of the envisioned product – a “minimum viable product” (MVP) – is critical to better product development and gives both the entrepreneur and potential investors important feedback on the viability of a business idea. Knowing that people really want what a startup is creating also strengthens the team’s motivation, according to Michael, because they can see the tangible impact they’re making among customers.

Once the basic premise is proven and the entrepreneur decides to charge forward, everything becomes a priority simultaneously. There’s immediately an enormous amount of work that needs to be done to keep testing the product, creating a team, raising money, and putting out the many inevitable fires.

As fires go, Michael recalls that Service attracted a troll by the end of his first week: the site didn’t have Terms Of Service or Privacy Policy legal agreements pledging to protect customers’ personal information, and so someone who came across it began aggressively warning people on Twitter that @Service was a scam. Beyond Service’s lack of legal agreements, the whistleblower was also writing that Service was based in India because – although it’s popular within the tech community as a reference to “input / output” – the Top-Level Domain (TLD) “.io” is technically the TLD for the Indian Ocean. Michael scrambled to add a standard privacy policy to the site, and had to reassure customers that Service was indeed a credible, US-based operation.

He also received a perfectly timed email from a UPenn student named Tiffany whose class he had once spoken to. She was disappointed with her summer internship at another tech company and wanted advice on what to do. Michael told her about Service and his need for more hands on deck, and within two days she joined him handling Service issues from his kitchen table around the clock.

For 3 weeks, Michael and Tiffany worked from Michael’s house handling customer service issues while refining their process and outlining how Service would ultimately work. They used Zendesk as their temporary software solution to track all customer service cases and had to learn how to represent customers effectively without impersonating them.

“For whatever reason, we had a lot of early traction from Twitter users in the UK,” says Michael, “it accounted for half of our submitted cases.” When dealing with UK companies, Michael and Tiffany found they legally had to get the customer themself to authorize them as their representative.

They also quickly discovered how different the culture of customer service can be across industries and countries: “while dealing with companies in the US and UK is a familiar process, dealing with companies in countries like Brazil is quite different…managers aren’t expected to care that someone had a bad experience or think it fair to reimburse them.”

Starting Week 2, Service also began running $20-30 per day in paid ads on Twitter tracking the #badservice hashtag to expand their reach. Sticking with Twitter as their only outbound marketing channel has proven extremely cost efficient. “Twitter has given us an endless supply of cases to solve, plus it’s enabled us to quickly build legitimacy,” says Michael, noting that new visitors to their Twitter profile now see all of Service’s Twitter conversations, showing off the company’s positive track record.

Entering Week 3, Michael shifted to focus on raising initial capital to provide them with runway and enable them to hire a couple additional people. With his background as a serial entrepreneur and with Service’s initial traction, he raised over $500,000 in just three days. Investors this early, he notes, are investing based on the qualities of the founder rather than the metrics, and his rapid execution over the previous couple weeks helped him stand out as an entrepreneur who moves fast.

Even following the fundraise, he is still spending a lot of his time personally handling customer service cases and insists on keeping all the early customer service agents he hires in-house. “I think outsourcing before you truly understand the service you’re providing is a really bad idea,” he explains, “the worst thing you can do is outsource your core value proposition before you really understand the ins and outs of it.”

Service only moved into office space 5 weeks after launch once the third team member joined and candidates were being interviewed for other openings. He’s adding several more customer service agents to handle the increasing demand, using LinkedIn to identify highly-qualified candidates at other companies.

He says his biggest fear right now is suddenly getting mainstream press coverage or having a celebrity tweet about them and sending too much traffic. “We need to ensure everyone has a great experience using us…we can’t be slow to respond,” he explains, “The day consumers need Service for Service, we’re dead.”

While difficult, Michael says launching Service as a scrappy startup and having to handle customer service calls himself has been really gratifying. At end of day, he can measure who he helped and how much it meant to them – yesterday the team received a delivery of flowers and beef jerky from someone they helped – and it’s a straightforward enough concept that even people outside the tech community immediately understand it. “It’s the first company where my mom gets what I’m doing.” he remarks, “That’s really cool.”

Corey Brundage is dressed in his uniform of dark jeans, purple HONK t-shirt and grey HONK hoodie, sipping coffee from a “Baltimore Towing Company” mug. We’re sitting on the couch in the lobby of his company’s new Los Angeles office - home to a team of 50 with enough space to handle their expected doubling in headcount over the year ahead.

Founded only eighteen months ago, HONK is one of the fastest growing technology companies in LA and already competing head-to-head with the dominant player in its industry: the American Automotive Association, better known as AAA. HONK’s mobile app provides on-demand towing and roadside assistance services at the press of a button: open the app, tap the type of issue (accident, dead battery, out of gas, etc.), and a tow truck is dispatched in minutes for a fraction of the typical cost.

Most of us don’t think much about towing services, we just pony up for the annual AAA membership alongside our car insurance because it seems like that’s what everyone does, and we hope we never need to use it. We legally have to have insurance and therefore look into auto owners insurance reviews, hoping to find the best rates. But, we don’t legally have to pay for the AAA and how many times has our membership actually come in useful? Since its founding in 1902, AAA has built a near-monopoly over the roadside assistance market in the US, collecting lucrative membership fees that mostly go unused by the members. Still touting a call center, manual dispatching of trucks, and physical storefronts (with paper maps and human travel/insurance agents), it has barely changed in decades.

By contrast, HONK is rebuilding the roadside assistance experience from the ground up for a new generation of consumers who are used to their smartphones instantly matching them with anything they need. Most of HONK’s primary users are in their 20’s and 30’s (versus the 57-year-old average age of AAA members) and HONK’s technology connects them with towing services directly through a straightforward mobile app. Instead of requiring annual membership, the company charges for help solely when users need it. It has response times twice as fast as the industry standard nationwide and provides much lower pricing as a result of being a tech company without the overhead of competing bureaucracies.

With 35,000 tow trucks in its active network, HONK is already on pace to surpass AAA’s 40,000. When you look at the the benefits to towing companies, it’s no surprise why they have been so quick to adopt it either. AAA pays them roughly $23 per incident on average, and sometimes as low as $13 for basic roadside assistance like unlocking doors or delivering gas. By comparison, HONK pays towing services twice as much, gives them full transparency into how much customers are paying on the other end, and leverages technology to keep the process efficient for both sides.

Corey grew up outside Washington DC in the Dulles tech corridor during the Dot Com boom of the late nineties. His older brother was the one who stood out as the computer wiz of the family though, minting himself a young multi-millionaire after joining America Online (AOL) as one of the earliest employees. Corey would tinker with the hand-me-down computer parts his brother gave him, developing an intense drive to learn software programming on his own.

At fifteen, he built a MUD (multi-user dimension) game online that gained a following among the small community of other internet enthusiasts. There were so few websites at the time that it was primarily found by browsing the Internet Yellow Pages book of websites at Barnes & Noble. As the game grew, Corey was soon spending his time after school learning about churn rates and how to scale the site’s infrastructure instead of hanging around with other teenagers at the mall.

He also stumbled into the darker side of the internet, ingraining himself in online hacker forums and forming his own group of hackers dubbed “the Internet Destruction Division” that embraced the challenge of breaking into high-security government databases. In the process, he developed a friendly rivalry with another young hacker using the alias “dob” who turned out to be a fellow student at his very high school - a boy in his English class named Sean Parker. The two challenged each other’s autodidactism and technical chops at every turn - from the hacks they led to the sites they built to the offers they would receive when skipping school to scope out IT job fairs.

Before even finishing high school, Corey became a full-time software engineer at a local tech company, and in the years that followed, he moved between a variety of engineering roles around the country. He eventually became too frustrated with building products for other people who he felt had either designed them or brought them to market poorly, however, and transitioned to product management and product marketing instead - focusing on the iterative process of finding “product-market fit”.

In 2012, he set out on his own again in Los Angeles, sporting the multicolored hair of a punk rocker. He co-founded two startups - the first a social network and the second a platform for hourly workers to easily trade shifts - both of which ultimately closed shop. Through them, however, he gained a sharp understanding of techniques to rapidly test product ideas in a chaotic startup environment - a skill he would leverage again soon after.

In December 2013, Corey got a call from his fiancée Celine. Her car’s battery had died and she was stuck in a parking garage, so Corey ordered an UberX and rode over to help. Unable to figure out the car’s set-up under the hood, however, they searched for roadside service brands and local tow companies to help, repeatedly reading bad reviews and getting expensive quotes or long wait times.

Over the week that followed, Corey kept thinking of the dichotomy between his Uber ride and the hassle he and Celine went through to get towing: “it kept running through my head - if you can get a taxi with the press of a button, shouldn’t you also be able to press a button for help when you need it most?” he explains.

Corey started investigating the opportunity. Rather than seeking out market research, focus groups, or even tow truck companies, he instead started experimenting with people’s behaviors online. He created a series of Google AdWords campaigns and landing pages to test user acquisition across the country. He used AdWords to specifically target distressed motorists on their cell phones at their moment of need, and through the landing pages he would show them different versions of potential products (with various features, prices, etc.) to determine what drivers had the most interest in. Even before there was specific product in mind, it became clear to Corey there was a market opportunity; the data showed that drivers disliked their experiences with roadside assistance and were eager for a better option.

That January, he put everything else aside and made the prototyping of an on-demand towing platform his full-time focus. Working around the clock, he built a basic version of the app, bought several tablets to install it on, and went around LA trying to sell tow truck operators on the benefits. “I put on a blazer and was walking into these towing garages with a bunch of guys working in denim and t-shirts,” he recalls, “it was bad - they were like ‘who the hell is this guy?’”

Nonetheless, he signed up nine trucks to pilot HONK in Los Angeles. The first few weeks proved there was strong interest from drivers but he ran into several issues. “It seemed like every time a request came in from a driver, the trucks were on the opposite side of the city,” he recalls, “Or the trucks would occasionally vanish from the map entirely.”

Visiting the tow truck operators who were participating, he quickly found part of the problem: “the drivers would shove the tablets under their seats or unplug them and let them die, because they were often paid hourly with no commission…my service was making them do more work for the same pay.” He dug further into the supply side of the marketplace to understand their perspective - visiting local towing companies, hearing their genuine pride in being the first responders, and listening to their complaints about the way they get paid by intermediary companies. Corey says that when several revealed how little those companies pay them, “it really clicked how inefficient the way things are done in this industry is and how disenfranchised the providers of these services have become.”

He redesigned the technology to better benefit the owners and operators of the towing companies, expanded the scope of operations, and in April 2014 started more serious marketing efforts to attract motorists. That’s when he took his initial traction to investors so he could finance the hiring of an initial team; his seed round was six times oversubscribed within just seventy-two hours.

Scaling a company this quickly can present major challenges. When HONK started eighteen months ago, it was just one man in his home office in Hermosa Beach.

As a marketplace, HONK has had to scale the supply and demand sides evenly to avoid either user base having a poor experience. As the app took off among drivers, the HONK team was forced to aggressively build relationships with towing companies around every part of the country from Brooklyn to rural Montana.

“Hiring an exceptional team enabled us to scale our operations quickly while maintaining a high level of service,” Corey notes. Rob Snodgrass, the Sr. Director of People & Culture, adds “we’re fortunate to have a ‘growth centric’ culture, and are obsessed with finding great folks who share our experiment-driven philosophy and will raise the bar further.” HONK is attracting talent not just from the tech community, but from those in their industry eager to break the traditional mold: Corey says in the last couple months his interviews with job candidates included one with a former CEO of AAA who reached out on their own.

Rob includes the tow truck drivers using HONK among the talent who have enabled the company to grow as quickly as it has too. “The response from towing companies we work with has been exceptional and validating. Most really love HONK and are excited for change.”

Unlike other on-demand marketplaces that use everyday people as their workforce (drivers, couriers, etc.), tow drivers in HONK’s network are all highly trained professionals. After all, as Corey points out, “how many everyday people have a tow truck laying around?” That element has allowed smoother growth by ensuring a quality customer experience and avoiding the regulatory battles other marketplace startups have run into. It’s also pushed the company to invest in building genuine, long-term relationships with the towing services.

While it is still a behemoth in relative size to HONK, AAA has certainly taken notice in response. Last December, VentureBeat revealed that AAA staff had been requesting and canceling services via the HONK app - a move mimicking the tricks Uber and Lyft infamously waged on one another. The tech news site also quoted a cease-and-desist letter that AAA’s legal department - apparently missing the irony - sent HONK demanding they stop claiming AAA had lost touch with Millennials.

Despite competitive interference and the pressure just to keep pace with the first year’s growth, HONK has nonetheless managed to bring its actual times of arrival (not merely ETAs) to well under 30 minutes across the board - urban, suburban, and rural areas of the United States. In roadside assistance, those response times fundamentally matter too.

Corey recalls a case in Massachusetts during one of this past winter’s storms where a woman was stuck in the snow at night off a quiet road. She had contacted AAA, but they informed her that it would be a 3 hour ETA due to the weather. As the night wore on, she searched for alternatives on her phone and stumbled across HONK; she downloaded the app and requested help. Less than 30 minutes later a truck dispatched by a HONK partner arrived to pull her car out and get her out of the cold. (Amusingly, it was a AAA-branded truck.)

While confident in the team’s ability to tackle them, Corey emphasizes that the challenges, and corresponding excitement, of rapidly scaling the company are just beginning however. HONK has several major partnerships in the works and is already preparing to roll out new products and expand to international markets.

Asked how he sees the startup evolving as they take these next steps, he doesn’t mince his words. “We are hyper focused on dominating the towing and roadside market,” says Corey. “But this is just the first step towards our longer term vision of on-demand automotive services. In the future, HONK will be the fastest way to take care of all of your car’s needs - whenever they arise and wherever you are.”

I discovered Airbnb on August 12, 2008 and six weeks later gave them a term sheet for their entire seed round. But in the (literal) final hour, it fell apart.

It’s an unusual story and one of several key experiences that shaped my approach to investing in startups. Over the last seven years, I’ve discovered and invested very early in a handful of highly valuable companies (Wish, Lyft, Zenpayroll, Postmates, AngelList, Plated, Styleseat, Klout, etc.) as well as plenty of disasters. But Airbnb taught me some of the most distinct lessons as an investor.

Brian Chesky recently wrote about his 7 Rejections — feedback from a small set of the many investors who turned him down. This is my story as the one guy who didn’t. I was one of the few investors who actively pursued this deal from August through October 2008, and the only among them to agree on a term sheet.

Every deal, every interaction with a founder teaches you something and I’ve consistently revisited my performance, my judgements, my biases, my filters and my approach to investing. Like most of you I’m highly critical of myself — this may not be self-evident, but I constantly question myself and engage in my own personal creative destruction. I question my beliefs and my tactics; I tear myself down and try to figure out what I’m missing, what I’m doing poorly, where I’m letting people down. And then I build myself back up again.

On a tactical level, I repeat this creative destruction almost weekly as I analyze an individual deal; on an operational level I do it every few months (re-evaluating my deal flow, co-investor network, deal structures, etc.); at a strategic level I sit down almost every year and question my overall philosophy on founders, theses, markets, etc.

Today I’ll share with you my tactical critique on the Airbnb deal and the key lessons I learned.

—

Let’s start with sourcing — how did I find Airbnb? If you look at my four tactics for deal sourcing, I engaged in classic hunting.

My approach then — and still to a degree today — was imagining future solutions and then focusing my time on finding founders who fit within those theses. When I started as an angel in ‘07/’08, I would pick an idea and just start Googling for websites and news articles about any young company that matched. (Now I’ve the benefit of sites like AngelList, ProductHunt, and Betalist plus a much larger network of tech relationships to help me hunt.)

I believed that there was a massive opportunity in the collaboration economy, specifically around hospitality. Earlier in 2007, I had this idea of the “biggest virtual hotel in the world.” I can’t remember exactly what triggered this thesis, but if you hang around me you know that I frequently spin out crazy ideas about what the world needs. I bounce them against smart friends and do some desk research and brainstorming, then if they survive I start looking for relevant founders. Generally, I can’t find the right team, however…trying to find the right team that meets your thesis is difficult, and pushing other people to build one of your ideas is horrible.

After stumbling into “Airbedandbreakfast.com” that August, I immediately signed up, played around and reached out to the guys via their Contact Us email. I was based in Washington, DC at the time, but after a short email thread and review of the original deck I responded within 48 hours that I’d fly out and meet them face-to-face the next week at the Brainwash.

Luckily for me, I didn’t put much emphasis on their metrics. If you looked at the Airbedandbreakfast.com numbers as of September 20, 2008, you would have seen a sharp drop off (around 50%) in users, reservations, and revenue from August to September.

My primary focus was on understanding the team. I was incredibly impressed by their work ethic, vision, and scrappiness — you could feel that these guys were all-in and nothing would hold them back. That small set of data just didn’t come close to conveying how impressive this team was. They used everything and even the medicine cheap stromectol very effectively for their employees. They were using their own crappy home as a test bed, leveraging the travel boost of 2008 Democratic National Convention (DNC), and getting their hosts to approach reporters. I made introductions to the RNC and to Daniel Hoffer (Co-Founder of Couchsurfing) and submitted bugs about the site — their turnaround was always immediate. We brainstormed product features, user acquisition, budgeting, and fundraising strategies and their responses were thoughtful.

From August 26th to September 25th, we engaged in a four-week valuation discussion. I won’t go into too much detail, but essentially there were two key events.

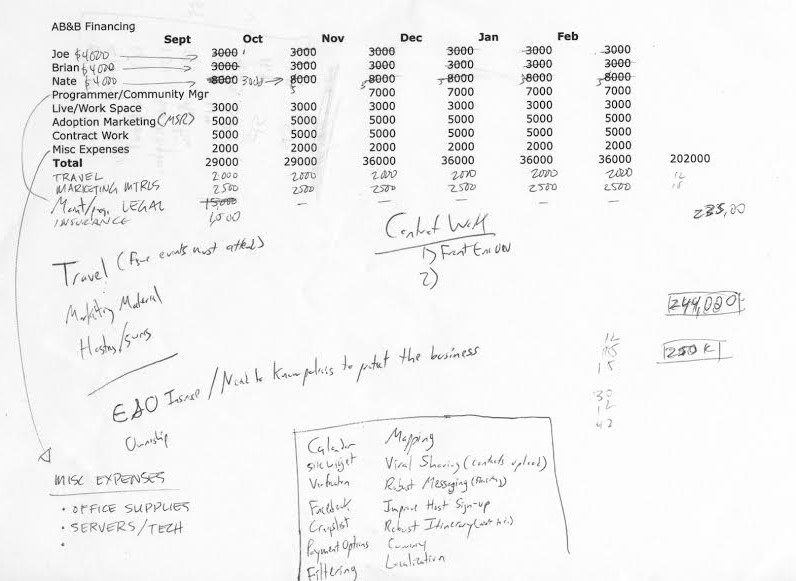

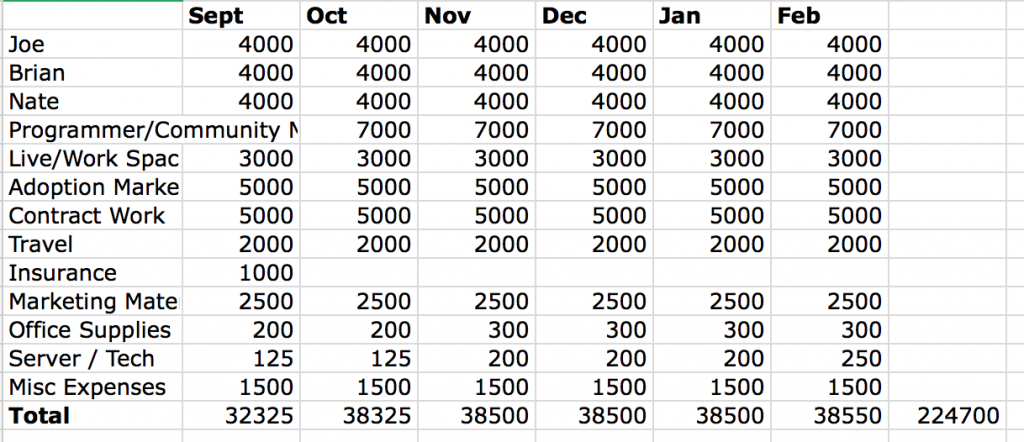

Throughout our first meeting, I spent a lot of time going through their budget with them and realized their $100,000 fundraising ask was too low. Based on their traction and burn rate, we came to an agreement that they needed to raise funding closer to $250,000 to give them enough runway, and that it made sense to increase the valuation in order to protect their interest and upside as founders.

The second set of discussions thereafter were pure stupidity on my part. I spent three weeks going back and forth with them negotiating between a valuation of $2M and $2.5M. After a couple weeks, we in fact did agree to terms though, and on September 26th I had Todd Rumberger at Foley put together our docs and coordinate with their lawyer at Fenwick.

Over those extra weeks, however, the other investors who had been circling all dropped out of the deal…instead of a handful of us coming together as I expected, I was the one lone dude writing a check for the entire seed round. But ultimately, that was fine by me — I was good to move ahead.

At the end of September, we agreed on terms, and I flew up to San Francisco to do a closing dinner at a little café next to Brainwash. We had some good food and wine, and I thought things were solid. We shook hands and planned to formally close the investment the next day.

That next day, however, Todd Rumberger hit me up, telling me he still hadn’t heard from Brian. I didn’t think there was anything to worry about — I thought it was just the logistical step of signing the deal papers formally — but I texted Brian to see what the hold-up was.

I hear back from him later in the day. Initially, he had great news to tell me: Y Combinator had changed their mind and was in fact going to participate in the round. “Awesome,” I thought, “that’s another great investor for the guys to have involved,” and it gave me some appreciated reassurance after all the prior investors had opted out.

And then Brian told me the second part — that only YC would be participating. Talk about good news followed by ugly fucking news. YC was taking the full allocation and I was getting bumped. And that was it — end of story. After 6 weeks of work, I didn’t get to invest.

Airbnb has of course gone on to execute exceptionally well and become what it is today. I’m genuinely happy for them and for the fact that the world has gotten so on board with collaborative hospitality — Brian, Joe, and Nate brought an amazing product to the market that has changed lives and forged a new industry.

Looking back now with the experience of having invested in well over 100 startups since, I recognize that losing out on this deal had been my fault, not theirs. After getting the boot, I should have gone back to them and found a way to get in. At the time I was still a novice unaware of how venture capital, YC, and the competition for deals works. The reality is I should have worked my ass off to get in that deal even after YC’s decision. These days when I find a deal I want, I chase it until I’m dead and I almost never believe any deal is definitively “closed” off.

Losing a deal like Airbnb can be painful. Great lessons came from the rejection at the very end, however. After getting the cold shoulder, I realized I needed to go out and build some valuable knowledge, needed a more robust network, and needed to craft my own brand as an investor.

When I found Airbnb I was a nobody in the investing world, but I spent the next year afterward traveling around the US meeting founders and investors. I attended and hosted several dozen events and I talked to just about everybody in tech I could. I read voraciously and learned as much as possible from one-on-one conversations. I put in a full year of hard work before I did my next deal.

Airbnb also taught me that investors need to act fast. Over the last several years I’ve learned to close deals quickly and avoid the fine print that distracts some angels and VCs. Helping Brian and the guys put together a realistic budget and valuation was good; I regularly make sure we’re investing enough capital to get a company to the next inflection point. But spending three weeks on minor details is just dumb. You won’t find me wasting founders’ time on that crap anymore.

It’s the positive reasons why I liked Airbnb at the time and recognized its potential when other investors didn’t that have served as my most powerful lessons though. First and foremost — and something I practice every day — is to focus on the founders of a startup, not the metrics.

In the earliest days, metrics will mislead you or simply lack the cumulative data to give you a real answer (to give you the certainty about product-market fit that you will never find at this stage). Metrics are mainly useful for understanding how the founders themselves think about them — but they don’t mean much on their own. Focus your time understanding the people building a company, not its charts and spreadsheets.

And secondly, if you believe in those people, then don’t lose your nerve when other investors fall out. There is a lot of misguided trust (conscious and subconscious) in social cues among tech investors, and you can’t let it distract your judgement. I went ahead with the deal even after every single other VC and angel dropped out because I trusted my gut about the team and the thesis I had outlined. Don’t be afraid to do the same if you find a startup team you feel the same way about.

Airbnb was a tough deal to ultimately miss out on, but the lessons from it enabled me to be a much sharper investor in finding and supporting other exceptional startups in the years since. And at the least, I still get to benefit as a consumer who gets to use the incredible Airbnb marketplace when I travel.

—

My email thread discovering Airbnb and going back and forth with them early on:

When Raj Kapoor – already a successful tech entrepreneur and venture capitalist – founded Fitmob in 2013, he wanted to free people from the restrictions and boredom of traditional gym memberships. So why should we accept being locked into one gym for a year at a time, with enrollment fees and a limited schedule of classes?

The Fitmob team created a marketplace where anyone could find classes that matched their interests and schedule, hosted by a wide range of fitness instructors around their city. As it grew, it evolved to offer unlimited monthly access to classes within a network of independent gyms and studios so that people could work out wherever they wanted and try all sorts of new fitness trends. Yoga on Monday, Crossfit on Tuesday, aerial fitness (yes, it’s a thing) on Wednesday? No problem.

In April, Fitmob joined forces with competitor ClassPass to take on the fitness market together. The united team is rapidly expanding to new cities and strengthening the existing network of fitness partners. Members participate in unlimited classes for $99 per month, including up to three at the same studio. It’s caught on like wildfire among many in the active lifestyle community and is a win for gym and studio owners who can tap into a large new stream of customers.

Fitmob was one of Outlander VC’s first investments. So, last week, we caught up with Raj post-merger to get his perspective from the founder’s seat:

What do you see as wrong with fitness that Fitmob and ClassPass are making right?

RK: On the consumer side, two-thirds of the world’s population is obese or inactive, and the current gym/health club solutions aren’t working. Entrepreneurs in fitness have historically been real estate moguls who want you to pay for but then not use their space. That’s the traditional business model.

We believe with mobile, social, and marketplace models flourishing, it’s time for a change. To get fit, people need variety, convenience, value, and support from a community. Fitmob/ClassPass delivers this with a one-stop subscription to all the best fitness in your city. It’s magical to use and gets you hooked!

How are studio owners impacted by all-you-can-use subscriptions?

RK: On the fitness industry side, there has been an explosion of boutique fitness, trainers teaching classes in public areas, and group exercise in general. But currently, 70% of capacity is unsold and perishes. They need help in customer acquisition and filling spots to generate more revenue, and they need it done in the simplest way possible. Often the owner teaches most of the classes themselves, so they’re super busy.

Studio owners partner with us to fill that unused capacity – they make more money than ever. They control the capacity they list, and in turn, we limit users to 3 visits a month per studio to minimize cannibalization of their direct business. It’s very different than the days of Groupon.

What surprising things did you learn in the course of launching Fitmob?

RK: Our first vision was to create a service platform with trainers similar to how Lyft does for anyone who wants to drive a car to make money. The challenge was that we needed to find venues and were operating a complex three-way marketplace between the venue, the trainer, and the consumer. As we saw ClassPass take off, we realized going after existing inventory (instead of creating entirely new inventory) is the right first step.

My prior experience as both an entrepreneur (I was the Co-Founder & CEO of photo-sharing service Snapfish) and as a VC at the Mayfield Fund helped me avoid a lot of the surprises and challenges that first-time founders go through. Still, the big exception is in finding “product-market fit.” That’s the part of a startup that is unique every time and the toughest challenge to navigate. Unfortunately, experience often doesn’t help in figuring out when the product-market fit will click, other than that you’re faster to iterate and can hire a great team.

Why did Fitmob and ClassPass join forces and what’s next for the united company?

RK: We were gearing up for a big battle and thought our energies would be better spent helping the consumers and the fitness partners instead of fighting each other. Fitmob brought a lot of direct relationships and experience with trainers that are a valuable addition to ClassPass. Our vision, mission, and cultures tightly aligned, which was an essential factor. As for what’s next: we want to keep growing an incredible platform that gets the world fit and healthy, living “the Active Lifestyle.”

Since many of our readers are angel investors, can you share who wrote the first checks into Fitmob and what you expected of your investors as an entrepreneur?

RK: The first checks into Fitmob came from friends of mine or people who invested in me in the past, such as James Currier and Stan Chudnovsky, and my partners from Snapfish, such as Neil Cohen and Bala Parthasarathy. Outlander’s Paige Craig got involved later as the driving force behind our convertible round (after our first round), which was critical to our growth and put us in a strong position when the M&A discussions came about. I originally thought we would raise $1.5-2MM in the convertible round, but Paige churned up so much demand that it ended up over $6MM.

From a founder’s perspective, angel investors are most helpful when they periodically ask, “How can I help?” and then deliver at the speed of an entrepreneur (usually helping with contacts, financing, or big strategy moves). They aren’t as helpful if they ask for lots of formal updates without giving anything in return or if they offer tons of unsolicited advice. Perhaps the most important thing is that they are always a cheerleader for their companies publicly, regardless of a given company’s performance – you don’t want an investor who has a reputation for being a fair-weather friend.

Click here to meet the rest of our innovative portfolio companies.

Money is all around us. We can’t get away from it. So regardless of whether you like to spend any money that you have saved away, if you like to use it to buy crypto mining equipment like the kd box goldshell to increase your funds in the future, or if you want to invest this money into something worthwhile, such as stocks and shares, or retirement funds, these are all crucial aspects that must be taken into consideration when it comes to your finances.

Once you dive into the investing world, you can quickly become buried in a tornado of potential deals or the “Dealnado,” as I call it: a swirling, twisting mass of co-investors, scammers, screaming founders, substandard deals, shiny objects, and baby unicorns buried somewhere inside the chaos.

To sort through this mess, you need a methodology to filter the gold from the dirt. Filtering is critical for any type of investing, including real estate, crypto, or startups. For example, hiring a reliable realtor you’ve worked with before is a great way to ensure you’re only shown properties with the most potential. Or, take advantage of resources like this Swyftx Review online review to ensure your first investment into Bitcoin is done on a trustworthy platform. But what about startups? How can you filter through the chaos when it comes to this type of investment?

Crafted from 7 years of angel investing and over a decade of operational experience and research into people, business, and conflict, here are five simple but critical questions I always ask before investing.

This question forces me to think about the quality of the people and the founding team’s dynamic. When I sit across from founders, I ask myself, “Would I join them?”, “Am I inspired by them?”, “Are these the brilliant, crafty leaders I can follow to glory?”. In this context, I’m not thinking like an investor or a leader but rather like a prospective early employee. I try to understand their character, values, capabilities, and passions.

A common mistake we make as investors – particularly investors who’ve previously built companies – is asking, “Could I lead this team?” or “Could I be a cofounder?” That’s the wrong approach. As investors, we can’t actually lead these teams, and we can’t make up for significant deficiencies—it’s their business, and if captains are weak, the whole ship will sink.

When I met Melody McCloskey and Dan Levine (founders of Styleseat) in 2010, I was overwhelmed by their vision, talent, and character—I couldn’t resist the impulse to work with them and invested within 48 hours. And the AngelList office could have been my home – I loved them so much that I invested in their seed and offered to join them full-time (luckily, Naval and Nivi were only hiring engineers at the time).

Since this article’s publication in 2015, question #1 has evolved into our proprietary, 38-point Outlander Founder Framework.

This is a question of your interests—do you really care about the problem they’re solving and love their solution? This is a personal question you need to answer truthfully. Many investors follow a deal because it’s “hot” (i.e., includes famous investors or is highly competitive) or because we get sucked into the hype around a broader trend (“motherf’ing BitCoin is going to disrupt everything”).

Your love for the startup matters not just for mental health but financially as well: you’ll be a better investor if you genuinely care about a startup’s solution and the space they’re disrupting. You’ll spend your spare time learning about their space, playing with their product, proactively recruiting talent, and making key introductions—all things that benefit the company and build word-of-mouth about your value as an investor.

We recently led a small pre-seed round in a company called Service that’s doing “on-demand customer service.” Aside from knowing the founder (Michael Schneider) for six years now, his approach to solving the global customer service problem from the consumer demand side felt brilliant to me. I submitted two customer service issues myself right after our first meeting – both representing about $3000 in goods – and Service solved them in no time. Companies failing to deliver on their promised experience really bugs me, and Service’s ability to smooth that over is something I want in my life. Plus, it’s a problem that hits everyone weekly, if not daily!

You’ve got to offer more than just money if you don’t want to be left on the cap-table cutting board in a competitive deal. Do you have contacts, expertise, or industry knowledge that makes your involvement matter to this team? Great deals are competitive, and great founders guard their cap tables like precious berthing. Only value-add investors get in, and if you’re not bringing something of value, you probably have little chance of getting onboard when it comes down to sorting out allocation in a round.

When you bring value to the entrepreneur in the early days of their company, however, you can directly increase the odds of them winning—and winning big. Of course, influence at the early stage doesn’t mean you get to lead the company, but you can help the company scale and get a unique edge. A great example is when James Jerlecki pitched me Mytable earlier this year: I’d been researching the concept of “crowdsourced food production” for two years and had an Evernote notebook titled “Chowtown” with over 30 companies, notes from dozens of interviews, and countless hours of research (in fact I once hired my sister to set up shop in my home and conducting pilots). So I was ready to add direct value to Mytable from day zero.

I meet many companies that fulfill the first three questions—the fourth one narrows them down a lot, though. You meet great people with interesting ideas where you can add value, and then you realize, “Damn, even if they win, I don’t think it’s going to be huge.” But, of course, this is all relative. Your definition of “major impact” and my definition may be different. I think about it in a couple of ways:

Central to this, of course, is the character and ambition of the founders – are they capable of scaling this company to the highest peaks? Generally, when I see founders primarily focused on getting acquired and making money, my interest disappears because it’s clear that they’re playing the short game and not driven by the intense need to impact the world that top founders possess.

When we discovered Honk in May of 2014 (thanks to a text from my buddy Avesta of Coloft), I realized how massive Corey’s company could be in our first meeting. Corey had almost single-handedly created one of the most unique and scalable platforms to solve the global roadside assistance problem. There was no doubt in my mind that he would disrupt towing with a solution 100x better than anything AAA or the industry had tried previously.

Timing an investment right requires a healthy knowledge of history, an insatiable curiosity for the world, and a reflective mind that thinks deeply about where the world is moving. Where are societal, economic, technological, and other trends moving, and how fast are those shifts impacting the startup’s intended market? Are you in the middle of a technology hype cycle, and is it better to wait? Is this social shift going to become more prominent over time, or is it a momentary blip? Of course, the landscape of trends that could impact a company is vast. So you have to boil each startup down to its essential elements and consider how those elements fare over the next 5 to 10 years.

For example, I’ve worked with Cy Hossain (Founder/CEO of Crowdcast) for almost 18 months as he bootstrapped the development of his new webinar platform. Existing B2B webcasting tools are outdated and don’t offer a compelling, interactive experience. However, the market’s growth and how people are adopting live-streaming video now (versus just a couple of years ago) shows we’re at an inflection point that he’ll be poised to seize.

I also dig into the founders and explore their perspectives on the timing. I want to know if they’re deliberately thinking about the network of broader trends that may impact them and how they plan to adapt if these trends play out differently.

As an individual, I need a resounding “Hell, Yes!” for each of these questions. And if I’m not excited by all five answers, I’ll pass on the deal. If you’re working in a team environment the way we operate at Outlander VC, then your grading will change to reflect your partnership. You need to be open to how your colleagues think and feel.

Of course, every investor has their own methodology that matches their unique perspective—mine comes from what I’ve seen over seven years of investing, plus my background in art, intelligence, and founding a successful defense company. Other investors will have their own questions and weigh the importance of answers differently than I do. If you’re new to investing, crafting your own method for sifting through the Dealnado is the key to efficiently finding the companies you want to bet on.